How the Climate Crisis Is Impacting Bangladesh

Few countries on Earth so exemplify the deep inequity of the climate crisis as Bangladesh.

Despite producing only 0.56% of the global emissions changing our climate, Bangladesh ranks seventh on the list of countries most vulnerable to climate devastation, according to Germanwatch’s 2021 Global Climate Risk Index (CRI).

This threat is not an abstract one. The data shows that from 2000 to 2019, Bangladesh suffered economic losses worth $3.72 billion and witnessed 185 extreme weather events due to climate change.

The story of how that came to be is in many ways a story about geography.

Located east of India on the Bay of Bengal, the country is known for its many waterways, including the world-famous Ganges river. These are waterways that produce rich agricultural soil, allow extensive travel by boat, and provide access to the rest of South Asia and the world.

What’s more, Bangladesh is home to the Sundarbans: the world’s largest contiguous mangrove forest. This UNESCO World Heritage site both provides a livelihood for local people and makes world-renowned biodiversity possible.

(A bountiful Mustard crop field in Sirajganj, Bangladesh.)

(A bountiful Mustard crop field in Sirajganj, Bangladesh.)

However, this same geography also makes Bangladesh one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to sea-level rise, increasingly powerful cyclones, floods, and more.

What’s more, a 2018 U.S. government report found that whopping 90 million Bangladeshis (56 percent of the population) live in “high climate exposure areas,” with 53 million subject to “very high” exposure.

The threat could hardly be clearer. So, here’s a breakdown of some of the major ways climate change threatens Bangladesh.

SEA-LEVEL RISE

Rising seas are a growing threat to people all around Bangladesh. That’s because a staggering two-thirds of the country is less than 15 feet above sea level.

For reference, the elevation of Lower Manhattan in New York City ranges from 7 feet above sea level to a high of 13 feet. And the threat becomes even clearer knowing that about a third of the population of Bangladesh lives by the coast.

It has been estimated that by 2050, one in every seven people in Bangladesh will be displaced by climate change. Specifically, with a projected 19.6 inch (50 cm) rise in sea level, Bangladesh may lose approximately 11% of its land by then, and up to 18 million people may have to migrate because of sea-level rise alone.

Looking even further down the road, Scientific American describes how “climate change in Bangladesh has started what may become the largest mass migration in human history… Some scientists project a five-to-six foot [sea-level] rise by 2100, which would displace perhaps 50 million people.”

What’s more, these rising seas now threaten to inundate the Sundarbans — the mangrove forest in southern Bangladesh. This is a doubly dangerous effect, given that this coastal forest doesn’t just sustain biodiversity and livelihoods, but also shields Bangladesh from the worst of the region’s many cyclones.

(The Sundarbans mangrove forest in southwest Bangladesh.)

(The Sundarbans mangrove forest in southwest Bangladesh.)

But sea-level rise isn’t just a problem because of outright land loss. It’s also a problem because of salinization: the process by which salt infiltrates agricultural land, hindering crop growth by limiting their ability to take up water.

On top of increasingly ruining crops, salinization threatens the drinking water supplies of tens of millions of people in coastal communities. Consuming this salty, contaminated water can expose populations to health problems like cardiovascular diseases.

For context, in 1973, 8.3 million hectares (321,623 square miles) of land were affected by encroaching seawater. By 2009, the number grew to over 105.6 million hectares (407,723square miles), according to Bangladesh’s Soil Resources Development Institute.

Overall, salinity in the country’s soil has increased by about 26% over the past 35 years.

FLOODING AND UNMANAGEABLE URBANIZATION

It’s a well-known fact that, all around the world, climate change is making rainfall more erratic and often far more intense. In Bangladesh, this reality rings especially true.

This phenomenon of stronger downpours – combined with rising temperatures melting the Himalayan glaciers that feed rivers around Bangladesh – is leaving massive swaths of the country far more prone to devastating floods.

Increasingly, supercharged water levels in the Ganges-Meghna-Brahmaputra River Basin are destroying entire villages and hundreds of thousands of livelihoods. Devastation that contributes to over 10 million Bangladeshis already being climate refugees.

(Flood affected area in the Bandarban district of Bangladesh.)

(Flood affected area in the Bandarban district of Bangladesh.)

As UNICEF describes, “Around 12 million of the children most affected [by climate change] live in and around the powerful river systems which flow through Bangladesh and regularly burst their banks. The most recent major flooding of the Brahmaputra River in 2017 inundated at least 480 community health clinics and damaged some 50,000 tube wells, essential for meeting communities’ safe water needs.”

Of course, that example specifically describes the impact of flooding on children. But the takeaway is clear. Millions of Bangladeshis are having to uproot their lives and migrate because of overflowing rivers.

By one estimate, up to 50% of those now living in Bangladesh’s urban slums may be there because they were forced to flee their rural homes as a result of riverbank flooding.

Similarly, a study completed in 2012 of 1,500 Bangladeshi families migrating to cities, mainly Dhaka, showed that almost of all of them cited the changing environment as the biggest reason for their decision.

Overwhelmingly, when these migrants move into big cities, they don’t find refuge from rural climate challenges, but rather, more and at times worse problems. As the video below describes, they’re forced to settle into densely populated urban slums with rudimentary housing conditions, poor sanitation, and limited economic opportunities.

For context, take Dhaka: Bangladesh’s capital and biggest city. Dhaka holds 47,500 people per square kilometer, nearly twice the population density of Manhattan. Yet, nowadays up to 400,000 more low-income migrants arrive in Dhaka every year.

The riverine flooding and other climate impacts contributing to this unmanageable urbanization has no end in sight. Especially without serious climate action.

CYCLONES

The Bay of Bengal narrows towards its northern shore where it meets the south coast of Bangladesh. This “funneling” can both direct cyclones towards Bangladesh’s coast and make them more intense.

These effects – combined with the fact that most of Bangladesh’s territory is low, flat terrain – can make storm surges absolutely devastating.

(The Bay of Bengal “funneling” up toward the coast of Bangladesh. Maps Data: Google, Landsat/ Copernicus, SIO, NOAA, U.S. Navy, NGA, GEBCO, SK Telecom)

Over the last decade, on average, nearly 700,000 Bangladeshis were displaced each year by natural disasters, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. The annual number spikes during years with powerful cyclones, such as the following:

- Back in 2007, Cyclone Sidr struck the country’s coast with wind speeds of up to 149 miles (240 km) per hour, claiming 3,406 lives.

- Just two years later, in 2009, Cyclone Aila affected millions of people, claimed the lives of about 190, and left about 200,000 homeless.

- In 2016, Cyclone Roanu caused disastrous landslides and submerged villages, leaving thousands homeless, forcing half a million people to evacuate, and causing 26 fatalities.

- Three years later, in 2019, Cyclone Bulbul swept through the country, forcing over 2 million people into cyclone shelters. Bulbul spent about 36 hours over Bangladesh, making it one of the longest-lasting cyclones the country has faced in recorded history.

- In 2020, Cyclone Amphan took the lives of 10 people in Bangladesh (and 70 others in India), left thousands homeless, and destroyed at least 176,007 hectares of agricultural land in 17 coastal districts. It was the strongest cyclone ever recorded in the country’s history.

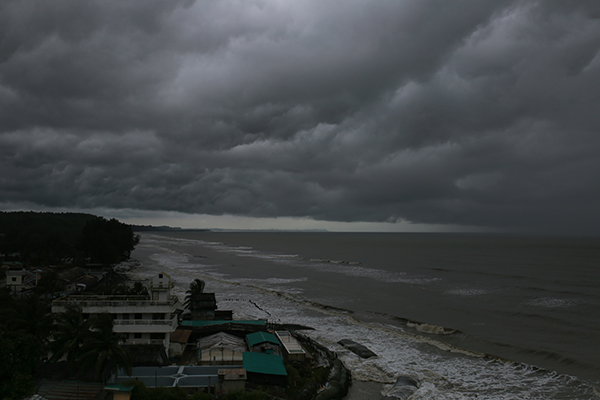

(A coastal storm rolling into Chittagong, Bangladesh.)

For a final example, just this year Cyclone Yaas made landfall with a wind speed of 93 miles (about 150 kilometers) per hour, like its predecessors, bringing momentous devastation, and claiming unnecessary lives.

Now, it can be easy to get lost in the numbers, especially when they’re so overwhelmingly large. But the takeaway is clear: Stronger cyclones are becoming more common because of our changing climate. As a result, Bangladesh is bearing more and more of the same tragic aftermath.

CLIMATE INJUSTICE

Talking about climate impacts in Bangladesh would hardly be complete without mention of the staggering injustice Bangladesh faces. Because overwhelmingly, climate impacts are being imposed on Bangladesh by high-emitting, wealthy countries — not by the people of Bangladesh themselves.

As a country, Bangladesh emits only a tiny fraction of the greenhouse gas emissions causing climate change. Perhaps more telling, the average person in Bangladesh emits 0.5 metric tons of CO2 per year. In the US, for comparison, that number is 15.2 metric tons per person — about 30 times as much.

JOIN OUR MOVEMENT FOR CLIMATE SOLUTIONS

For Bangladesh, for so many other countries, and for everyone’s shared future, the time to act on climate change is now.

Fortunately, we can still make a world of difference.

So, are you ready to make a difference for the future of our planet?

Across the country and around the world, everyday activists supporting sustainable solutions in their communities are making the difference in the fight against the climate crisis. That’s why we invite you to learn more about our Climate Reality Leadership Corps.

Climate Reality Leadership Corps trainings are where people just like you become world-changers. You'll spend three days learning from former Vice President Al Gore and a host of thought leaders and pioneering activists how we can solve the climate crisis together.

Click here to learn more about joining the fight.

By Diego Rojas