Our Smoke Signal

It was New Year’s Day, 2020.

Setting off down the scree slopes of Mt. Angelus, New Zealand, I didn't notice the smoke at first.

The previous day, we had climbed through clouds for hours until emerging at 1,650 meters to a spectacular view of a clear blue sky and the hut resting alongside Lake Angelus, where we welcomed in the New Year.

To all of us in the Climate Reality community, we know 2020 marks the start of a critical decade. I’d been looking forward to a short hike with my partner and his family in NZ before flying home to continue my work on climate solutions in Australia.

For two days, my focus was instead on navigating trails, taking in vistas, hearing fellow traveler’s tales, and at points, pushing aside the pains that come with lugging a pack up a mountain to those of us that lead more office-dominated lifestyles.

The Mt. Angelus landscape, reminiscent of The Lord of the Rings, worked to toughen my resolve by reminding me of two hobbits’ discussion as they approached Mordor. Frodo faces yet another obstacle to destroying the ring and is close to giving up when he asks, “What are we holding on to, Sam?” To which Sam responds, “That there's some good in this world, Mr. Frodo. And it's worth fighting for.”

With the scenery reminding me of the good in this world, I was even more determined to return to Australia to try and try again to raise the nation’s ambitions on climate.

As we descended the ridgeline toward the car, I noticed the red glow of the sun. Before long, I recognized an all too familiar scent from growing up in rural New South Wales (NSW), Australia. Bushfire smoke. But here in New Zealand? Strange. My steps slowed. Perhaps, I was just tired.

Back in the car and on the way to Wellington, my phone buzzed with notifications of the horrors in the news back home. I pulled up the NSW Fires Near Me app and saw icons everywhere across the state – the smoke we were seeing had blown thousands of kilometers across the Pacific Ocean.

My data was low, so I’d need to wait for WiFi before I could call my family.

The next day, I called my brother. Stresses at work from road closures due to fires in the Canberra region – but otherwise okay. My sister was far from the fires in Western Australia, but keeping an eye on a cyclone developing off the coast.

My mum’s farm, on the outskirts of Candelo in NSW, was in a “watch and act” zone. Engulfed in smoke, she and her partner had been on ember watch and hadn’t slept much, clearing burning leaves from around the house and off the roof blowing over from the mountains ablaze more than 50 kilometers away. They’d set up the water tank and a generator on the truck. Her voice sounded shaky.

Luckily, they had recently de-stocked their paddocks due to the drought. So now their main worry was the house, with its natural gas tanks, wooden verandas, and nearby row of tall pine trees. Mum had spent the past few hours raking up wheelbarrows full of dry nettles.

“They’re nearly dead from the drought. Perfect tinder,” she sighed as she caught her breath, updating me for the second time that day. “I’ve thought about removing them so many times – I’m allergic, you know. Too late now, anyway.” She described how she was putting out sprinklers and hoses to wet the ground around the house. “Hopefully that does the job,” she said, uncertain.

The next day, mum sent through this video:

From my in-laws’ house in Wellington, I was glued between my laptop and phone for the rest of the day, feeling my sense of powerlessness grow. Had she talked to her neighbors? What was her escape plan? Would she go to the evacuation point in the village? Did she have woolen blankets and water in the car in case of an overrun?

“Yes, yes… I’ve packed everything we need. We will be okay.”

I told her I wished I was there to help – and was secretly terrified by the thought of being where she was. My conversation sign-offs included “I love you,” a phrase not often uttered in my stoic, conservative family. Over the coming days, the wind changed and saw conditions improve for her region. Mum’s house, inside and out, was covered in black soot. But they were safe for now.

At first, I couldn’t reach my dad. I knew, since he’s a long-serving fire captain in NSW, he was likely busy fighting the fires. Before Christmas, he’d told me he was “sick of these smoking tours into the bush.” I received some WhatsApp updates. He’d spent New Year’s Eve at a fire front, and led a couple more strike teams since. He described outside his home as “very smoky, like a London fog.”

It's February now, and back on the phone with my dad, he described his humbling experience of being invited aboard the HMAS Australia as a special guest to honor firefighters for the Australia Day Sydney Harbour ceremony last weekend. There, he met people like the NSW assistant fire commissioner, who he’d previously referred to as a city-dwelling bureaucrat. Following a conversation on the HMAS, he described him as “a good bloke.” He told me he knows people give them a hard time and mentioned the assistant commissioner “knows a bit about fire.”

Chatting with my family I often mention that the news is worrying me.

I ask if they’ve seen fires like this before and what they think about them becoming more extreme from a hotter and drier climate. I listen patiently and ask questions. Often, I hear them echo lines from media outlets and politicians skeptical of the need to act on climate change. It makes me sad. Scientists have been warning of the link between climate change and more frequent and intense fires in Australia for more than a decade. But even the extent of the fires doesn’t lead them to feel the same sense of urgency I feel about our need to address the climate crisis.

It’s been one month since I descended from the peace of Mt. Angelus to the devastation unfolding at home. Like everyone I know, I’ve been grieving. The blue mountains I never explored. The loss of my great uncle’s orchards that I used to visit as a kid. The NSW south coast villages and their surrounding forests and wildlife I've studied and love.

Living in Brisbane in southeast Queensland, I've been relatively lucky. A few days of smoke from burning nearby rainforest in November burned my throat as I cycled to work. To the west of Brisbane, further loss of places I was hoping to one day see were charred skeletons as I drove through just last week.

Recent rain has sheltered the Brisbane region from further devastation. The Queensland government's emergency services division recently announced its shift in focus to cyclone and flood preparedness.

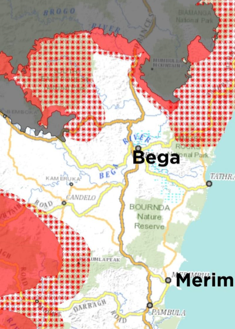

For my mum in southern NSW, the last few days have seen fire conditions worsen again. Another out of control fire is heading toward the farm – this time from the east. Once more, she must pack, watch for embers, and have the generator, pump, and hoses at the ready. Looking at the predicted path map, again I worry for her safety and wonder, Where can any surviving wildlife flee to?

Map Data © 2020 Google; © State of New South Wales (NSW Rural Fire Service). For current information go to www.rfs.nsw.gov.au.

Map Data © 2020 Google; © State of New South Wales (NSW Rural Fire Service). For current information go to www.rfs.nsw.gov.au.

Across the nation, the smoke and the fires are on everyone's mind. The commentary is ongoing but still divisive and politicized. For Climate Reality Leaders across Australia, it’s a constant test of not only how we communicate, but of our tenacity too.

The loss and damage from the climate-fueled fires is inescapable. Public donations continue to roll in, exceeding any natural disaster response in Australia’s history.

For me, the year has started with a smoke signal to replace the smokescreen that’s been around climate change in Australia. This smoke signal is not only a call for help but a warning of what we have to lose and what we are fighting for. I just hope that the signal awakens Australia to the reality of climate change, and as a nation, we finally step up.

One month into 2020 and I’m glad for the days of peace I had atop Mt. Angelus, NZ. I'm also glad for the Climate Reality community.

I know it’s going to be a tough year and a tough decade. But I also know our community of Climate Reality Leaders will hold on to – and fight for – a safe climate.

Join Climate Reality’s email list and we’ll keep you posted on the latest developments in climate policy and how you can help solve the climate crisis.