“Because It’s Not on Us, Just Because We’re on the Front Line. It’s on You Too.”

As a kid growing up in Wilmington, a community just north of Long Beach, California, having catastrophic nosebleeds, asthma, and school friends being diagnosed with leukemia was simply part of life for Ashley Hernandez.

“We were always running around at school with tissues up our nose [to stop our nosebleeds],” she explains. “We’d be told ‘you can’t go outside, there’s been an explosion’, or ‘don’t drink the water’.

“When people think about LA, a lot of folks don’t think about Wilmington,” the 28-year-old environmental justice activist says. “They think about Hollywood stars, they think it’s the sexiest place you can be in. And that’s the biggest lie that anyone has ever heard.”

Wilmington, a neighborhood with less than 54,000 residents, produces one-third of California’s oil. Residents have complained of foul odors, headaches, miscarriages, gas flaring and oily dust, for more than a decade, ever since LA city planners granted permission to drill 540 new wells and produce up to 5,000 barrels of oil a day on one Wilmington site alone.

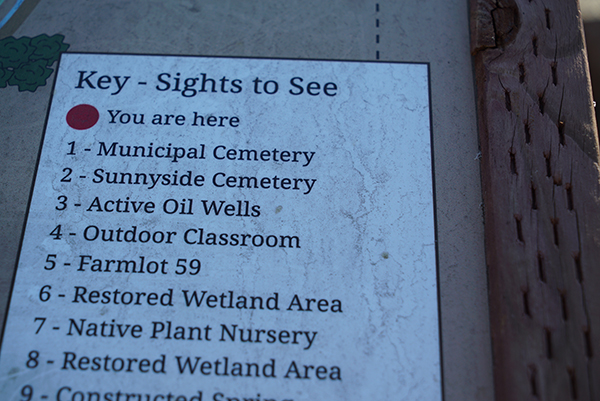

“It’s one of those things you can’t escape,” Hernandez, who works for Communities for a Better Environment continues. “You’ll see container yards right in front of cemeteries, oil drills next to churches, homes, day cares. It’s the physical representation of what environmental racism is.”

For all its sparkling veneer, Los Angeles is a city built on oil. America’s most glamorous destination also happens to be the US’ largest urban oil field, with the Los Angeles basin producing around 12 million barrels of oil a year as of 2019. Wilmington is home to one of the largest oil fields in the US, originally an estimated 3 billion barrels of recoverable oil in total.

Five million Angelenos – or one in three – live within one mile of an oil well, and 60% of them are Latino. Nearly 600,000 people in LA County live within a quarter of a mile of an active oil or gas well. The threat – and disparity – goes beyond the county. In California, over 2 million residents live within a half mile of oil and gas development; 92% of them are people of color.

The disparity in where these oil wells are located in LA county is environmental racism at its worst. Although drilling happens across the county, in wealthier areas like Beverly Hills the derricks and wells are camouflaged behind colorful towers, or fake office building structures. There were also stricter regulations on when, where, and how oil could be drilled – until a group of teenagers sued the city. The suit was first filed against the City of LA in 2015, arguing that: “drilling sites in South Los Angeles and Wilmington — neighborhoods where the vast majority of residents are black and Latino — are on average hundreds of feet closer to schools, playgrounds, and parks than drilling sites in neighborhoods such as West Los Angeles and Wilshire with larger numbers of white residents.”

The city placed conditions on drilling activities in the Beverly Hills area, such as enclosing the derricks in sound-proof structures. But over in South LA, they were drilling at all hours of the day, in plain sight.

The city eventually settled with the group of teens, which included leaders from the South Central Youth Leadership Coalition and youth members of the Center for Biological Diversity, and cracked down on the regulations in South LA. The teenagers and the City were later countersued by the California Independent Petroleum Association (CIPA), who said the oil companies had not had an opportunity to recognize their interests. “It’s disappointing that the rules were created without input from the entities that must comply with them,” a spokesperson said at the time. The case was later dismissed.

Three quarters of LA county’s active oil wells are within 2,500ft of residential buildings. The health risks of living so close to an oil site are deadly; those who reside near a well or refinery face elevated risk of cancer, something that Kimberley Amaya, a 23-year-old from Wilmington, knows all too well – her neighbor recently passed away from cancer. “It’s really prevalent in my community,” she says. “All we want is to have clean air to breathe. I shouldn’t have to fight for this, this shouldn’t even be a problem.”

The drilling process emits an array of toxic substances, including benzene and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons – which are carcinogens and may cause reproductive issues – and diesel exhaust, into the surrounding air and waterways. In 2017, research emerged to suggest that children who have been diagnosed with acute lymphocytic leukemia were 4.3 times more likely to live in areas with the highest density of active oil and gas wells.

The issues Wilmington residents experience are not unique to the area. Further north, in Culver City, lies Inglewood Oil Field, a sprawling 1,000-acre site, sitting atop a cluster of rolling hills, overlooking the city and adjacent to neighborhoods, playing fields and parks. The oil field has churned out between 2.5 million and 3.1 million barrels of oil every year over the past decade, according to its owners Sentinel Peak Resources.

“Urban oil drilling is an environmental and health justice issue,” explains David Haake, Chair of the Clean Break Team. “Due to decades of redlining, environmental racism, and indifference of elected officials, the majority of these oil fields are situated in low-income Black and Latinx communities from South Los Angeles.”

But there is hope on the horizon. Earlier this month, Los Angeles County supervisors voted unanimously to phase out oil and gas drilling and ban new drill sites in unincorporated areas, meaning more than 1,600 active and idle oil and gas wells face closure. Among the sites is Inglewood Oil Field, which is adjacent to a number of Black communities.

“There are tens of thousands of people who live in very close proximity to oil wells, 73% of whom are people of color,” Supervisor Holly J. Mitchell, representative of the district, said.

“So, for me, it really is an equity issue.”

For Hernandez, she hopes her community is simply heard. “I hope our story isn’t something that’s just forgotten about, I hope our stories are able to make it out of here. Because it’s not on us, just because we’re on the front line. It’s on you too.”