Drought and the Western United States: What You Need to Know

The western United States has been in the news a great deal recently.

A “heat dome” parked over parts of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and northern California in late June, bringing truly record-shattering temperatures to the region. This historic heat wave in the Pacific Northwest came just two weeks after numerous temperature records fell in Montana, Colorado, Utah, California (again), and other parts of the intermountain west thanks to another run of 100-degree-plus temperatures.

And just this past weekend (July 9-11, 2021), 31 million people in California, Arizona, Nevada, and more were under heat advisories or warnings as temperatures soared.

Heat waves and higher-than-ever temperatures like these have become a disturbing new norm in this part of the world.

In June of 2019, Las Vegas in Nevada had to set up shelters and temporary cooling stations after excessive heat warnings were issued by the National Weather Service. By August, the state had broken a record for most consecutive days over 105 degrees.

In the area near Phoenix, Arizona, deaths from heat-related causes are growing. In 2016, 154 people lost their lives to excessively hot weather; in 2020, at least 494 deaths were linked to high heat.

At the same time, parts of the western US are seeing less precipitation than they used to – in some cases, a lot less. And when the rain does come, more and more often it’s falling hard and heavy – and running off the sunbaked soil, sometimes overwhelming stormwater systems and eroding land along the way, all while the ground remains dry.

Unsurprisingly, this combination of factors has left nearly all of the region in an official state of drought.

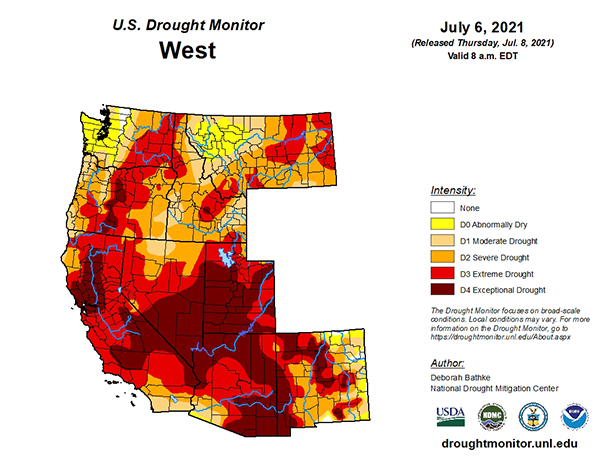

And when we say “nearly all,” that’s no exaggeration: 90% of the American West is now in varying states of drought. In about half of the region, according to the United States Drought Monitor, drought conditions are so bad they are considered either “severe” and even “exceptional.”

The US Drought Monitor is jointly produced by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the United States Department of Agriculture, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Map courtesy of NDMC.

What is Happening?

While droughts can have different causes depending on the area of the world and other natural factors, most scientists have started to link more intense droughts to the climate crisis.

As more greenhouse gas emissions are released into the air, more heat energy from the sun gets trapped in the atmosphere and air temperatures increase – leading to more moisture evaporating from the land and nearby bodies of water. All the while, this same warming is fundamentally altering the water cycle all around the world. The result: shifting precipitation patterns that have made rainfall either increasingly abundant or in desperately short supply, relative to longtime averages, in many areas.

Warm weather is also arriving earlier and earlier and lasting longer. It goes to figure that snowpacks in the US’ western mountains are melting earlier too, leaving less water available during the heat of the summer.

“Areas that might have normally gone a few weeks without rain may now go a few months without a drop. In the mountains, more precipitation falls as rain rather than snow, decreasing snowpack,” the New York Times reports. “Even a decent snowpack melts faster now, making it harder to manage water supplies. And soils and vegetation lose more moisture as temperatures rise.”

Less Water, More Problems

It’s often said that a picture is worth a thousand words, so let’s start with this one:

Credit: Rebecca L. Pittman – Getty Images

This is one of the fingers of Lake Oroville, the second largest reservoir in California. We trust you can tell where the water is supposed to be?

Now, consider this (from the Associated Press):

Each year Lake Oroville helps water a quarter of the nation’s crops, sustain endangered salmon beneath its massive earthen dam, and anchor the tourism economy of a Northern California county that must rebuild seemingly every year after unrelenting wildfires.

But the mighty lake — a linchpin in a system of aqueducts and reservoirs in the arid US West that makes California possible — is shrinking with surprising speed amid a severe drought, with state officials predicting it will reach a record low later this summer.

(Emphasis ours.)

Indeed, water levels at this vital reservoir are expected to get so low that in June 2021, it was announced that a hydroelectric plant powered by water from the lake would be forced to shut down for the first time ever – right at the height of the summertime, when demand on the electrical grid is particularly high because of home and business air conditioning.

When operating at full capacity, the Edward Hyatt Power Plant can power up to 800,000 homes. But dwindling water supplies mean that come August, it won’t be powering any.

Elsewhere, the water in Lake Mead, the vast reservoir on Nevada’s border with Arizona, sits at just 35 percent of what the lake can hold. That has a lot to do with the diminishing river that feeds it – the Colorado River, which more than 40 million Americans depend on for drinking water, irrigation, and much more.

To fully grasp the impact our changing climate might have on a river like the Colorado, you should start at its literal source. Much of the water flowing down the river originates as snow high up in the Rocky Mountains.

But as previously mentioned, the high-elevation snowmelt that constitutes the headwaters of the Colorado is shrinking. With spring seasons arriving earlier and earlier, and with highly variable annual precipitation, mountain snows simply cannot keep up with the rising demand for water downstream – especially when the spring and early summer rains never show up to play their part.

Impacts

Climate crisis-exacerbated drought is putting a drastic strain on water resources across the US west – with major consequences for people living in communities throughout the region. It’s climate change doing what it always does: making an already bad situation much, much worse.

Water is, of course, the key factor in all agriculture. So the success of family gardens, the livelihoods of farmers, and the availability of fresh, affordable food everywhere is directly threatened when our climate changes and water becomes desperately scarce in any particular region.

There are also other consequences of drought that you might not immediately think of – like the increased risk of wildfires.

The climate crisis creates the perfect conditions for extreme wildfire seasons in the American West and many other regions around the globe. The reasons why are pretty simple science, and they’re going to sound familiar: Warm weather is arriving earlier and lasting longer. Snowpacks are disappearing earlier. Precipitation patterns are changing.

The result? Parched land and withered plant life.

All these dead and dried-out plants then act as tinder, igniting when the heat soars, as it has so acutely in recent months, and lightning strikes – and it’s striking more often as our climate changes. Plus, with less predictable rains, and seemingly more unpredictable wildfire behavior, once fires begin, they are getting harder and harder to stop.

And of course, we haven’t even mentioned drinking water.

“The people who manage the West's complex water systems are realizing that with climate change, they can no longer rely on the past to predict the future,” according to NPR.

“That's creating a fundamental threat to the way Western water systems operate, because they were built around the idea that the climate would remain constant. Historical climate data such as river flows and rainfall totals told engineers how big to build reservoirs and canals. The data also told them how much water was available to divide up among cities and farms.”

Key Takeaways

- Longer-lasting heat waves and higher-than-ever temperatures have become a disturbing new normal in the Western United States.

- These temperatures – alongside changes in precipitation patterns, earlier-than-ever snowpack melt, enhanced evaporation, and other climate impacts – have plunged nearly all of the region into a state of drought, which is so bad in some places it’s considered “extreme” and even “exceptional.”

- Some of the most important reservoirs in the western US currently sit at less than 40% of their capacity.

- Drought is linked to crop loss on farms, wildfires, and problems accessing drinking water, threatening the lives and livelihoods of people throughout the West.

- The water systems of much of the American West were built on the assumption of a consistent climate and predictable rainfall and snowpack melt, and they’re struggling to deal with substantial declines in both across the region.

What You Can Do

Drought has serious consequences for people’s lives and livelihoods, affecting everything from agriculture and drinking water supplies to transportation and health. And warming temperatures are likely to continue creating drier conditions for the next several decades in some parts of the world, including (perhaps especially) the American West.

But we can flip the script on the back half of the century – and create a better future for generations to come.

If we raise our voices together now for an infrastructure bill with climate and justice at its core, we can work toward 100 percent clean, renewable electricity by 2035 for the whole country. A zero-carbon, electrified transportation future. Pollution-free, efficient, and green communities. And so much more.

Join a Climate Reality chapter today and do just that as part of Our Climate Moment. The campaign is mobilizing activists like you across the United States to make Congress and the Biden Administration act quickly on targeted climate policy solutions.

Now’s the time to think big and act boldly to confront the climate crisis threatening our future. This is Our Climate Moment – and we can’t afford to waste it.