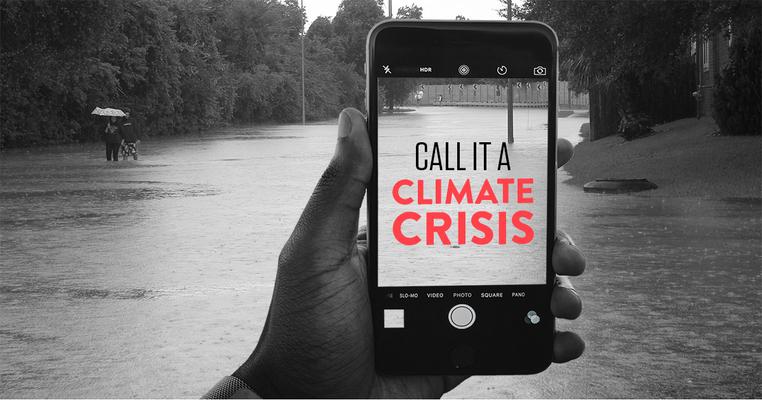

Why Do We Call It the Climate Crisis?

So when it comes to what fossil fuels and climate change are doing to our planet – throwing nature out of balance and putting us on the express lane to global catastrophe – we’re calling it like we see it.

We’re calling it the climate crisis.

The way we see it, it’s the only term that makes sense. After all, when lethal heatwaves become the new normal and kids can’t safely play outside, it’s a crisis. When reservoirs dry up and droughts stretch on so long that farms wither and our water’s at risk, it’s a crisis. When kids have to walk out of school for adults to see their future’s on the line, you bet it’s a crisis.

Then there’s the fact that the world’s best scientists are jumping up and down and waving their lab coat arms, trying to warn us that these and other impacts start going from bad to worst if we don’t slash fossil fuel emissions by 2030.

That we are approaching dangerous points of no return if we don’t act, everywhere from the continued existence of coral reefs to Greenland’s massive ice sheet melting and raising sea levels worldwide.

So yeah, what we’re facing is a climate crisis. And we need to start talking about it that way.

Why Fossil Fuel Interests Like “Climate Change”

Gentler related terms like “global warming” and “climate change” tend to fill most media and political discussions. But they’re just part of the story in much the same way that a car is just one part of a car crash.

Global warming, generally speaking, refers to an increase in average annual temperatures we’ve seen since the Industrial Revolution. Basically, the process of the world getting hotter overall since we started burning fossil fuels.

Climate change, on the other hand, is the shift in seasonal patterns we see as global warming throws nature out of balance. It’s how winters are not only seeing warmer temperatures but more extreme and frigid storms (polar vortex, we’re looking at you). It’s how the water cycle that brought snow and rain at predictable times of the year for generations isn’t on the same timetable in growing numbers of places. The list goes on.

Contrary to conspiracy theories, both terms have been around for decades. Skeptical Science traces “global warming” back to 1961 and a variation on climate change – “climatic change” – even further back to a 1953 paper.

According to NASA, the term “global warming” burst onto the public stage in June 1988 when scientist James Hansen gave widely reported and alarming testimony to Congress on the greenhouse effect and climate change, capturing the public imagination. That same year, “climate change” entered the highest levels of international policy with the formation of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

For fossil fuel interests, the difference between the two was not academic. In 2002, pollster Frank Luntz – the architect of the climate denial strategy challenging the scientific consensus – had a new idea for undermining popular support for climate action, advising then-President Bush:

“‘Climate change’ is less frightening than ‘global warming.’ As one focus group participant noted, climate change ‘sounds like you’re going from Pittsburgh to Fort Lauderdale.’ While global warming has catastrophic connotations attached to it, climate change suggests a more controllable and less emotional challenge.”

Luntz might have been onto something about the soothing sound of climate change. Either way, someone listened to his advice. The president would speak about “global climate change” but never “global warming.” Now even ExxonMobil has a statement on climate change (though the company seems to have forgotten to mention its part as a prime driver). Nowhere on the homepage, at least, does it use the term “global warming.”

Pointing the Telescope the Wrong Way

We’ll go one step further than Luntz and say it’s time to abandon both terms in culture. Not only do they both fail to evoke the urgency of the existential threat we face as the planet heats up, but they’re both focused on the wrong thing.

That is, think about either climate change or global warming and chances are, you’ll think of immense natural systems. You’ll think, maybe, about glaciers melting, but you’ll likely stop there. In either case, the problem can easily feel enormous and beyond what humans can touch.

What’s missing from this picture is, well, people. If we’re going to focus on solving this crisis, we need to focus on what it means for everyday working families, students, parents, and the people who live next door. We need to bring them into the picture to see how a warmer world is a dangerous world for all of us.

There’s more. We also need to talk about how a fossil fuel economy not only destabilizes our climate, but so often condemns low-income families and communities of color to inhale cancer-causing chemicals from oil refiners and fracking pipelines.

Most of all we need to act. Climate change might be something that’s happening, but the climate crisis is something we can act on. It’s something we must respond to. It’s the difference between a six-foot teddy bear appearing at your door – and a six-foot grizzly bear.

Notably, science backs this up. A study by SPARK Neuro found that hearing “climate crisis” generated at least 60 percent more of an emotional response in respondents than “climate change.” And you don’t need scientific research to tell you that when something provokes a stronger emotional reaction, it’s also much more likely to provoke action.

Where’s the News on This?

Sadly, not where it should be.

New analysis from Public Citizen shows that even when nightly news and Sunday talk shows do cover climate, their reporting almost always lacks the sense of urgency and gravity that an existential threat demand. In 2018, only 50 of 1,429 segments on climate (3.5 percent) referred to the threat as a “crisis” or “emergency.”

How the news treats climate matters. After all, words matter. The words reporters and anchors use to talk about the issue shape the perceptions of millions. If they’re not talking about climate as a crisis, entire communities and countries may not see it that way and fail to act. Now while we still have time.

We can change that. We’re calling on the major networks that bring us the news and help us understand the world to call this what it is. Call it a climate crisis. People need to know exactly what we’re facing.