Why Melting Ice in Antarctica is Making Waves

This past December, the massive Thwaites Glacier in Western Antarctica made headlines for all the wrong reasons. Specifically, because new research revealed that the ice shelf preventing it from sliding into the ocean and drastically raising sea levels could collapse well within the next decade.

This Florida-sized glacier had already worried experts for years, going as far as to regularly be called the “Doomsday Glacier”. And yet, this update from the scientific community was still groundbreaking.

It’s news that the world — particularly low-lying island and coastal communities — should understand and act on. So, what exactly is Thwaites Glacier, what does the latest research about it say, and what consequences could come from its decline?

FIRST THINGS FIRST, WHAT IS THWAITES GLACIER?

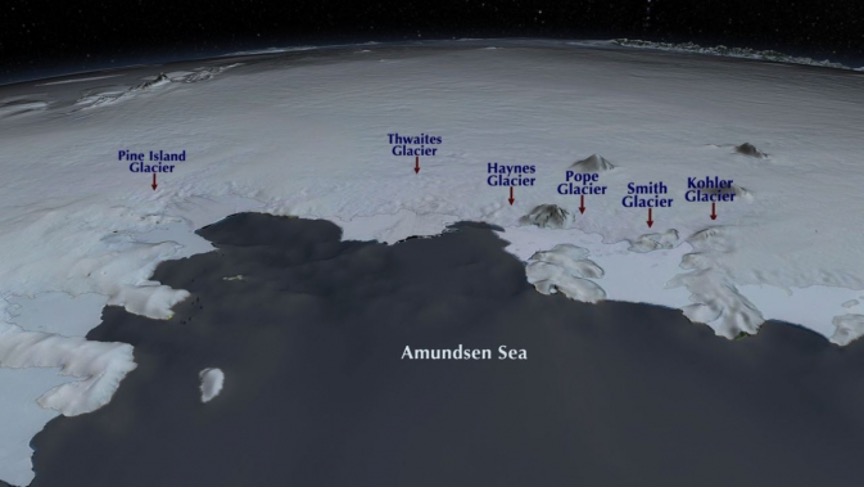

Thwaites Glacier is a massive body of dense ice located in Western Antarctica. Measuring about 80 miles (120 km) across, it’s the widest glacier on Earth.

Thwaites Glacier in Western Antarctica. Credit: NASA

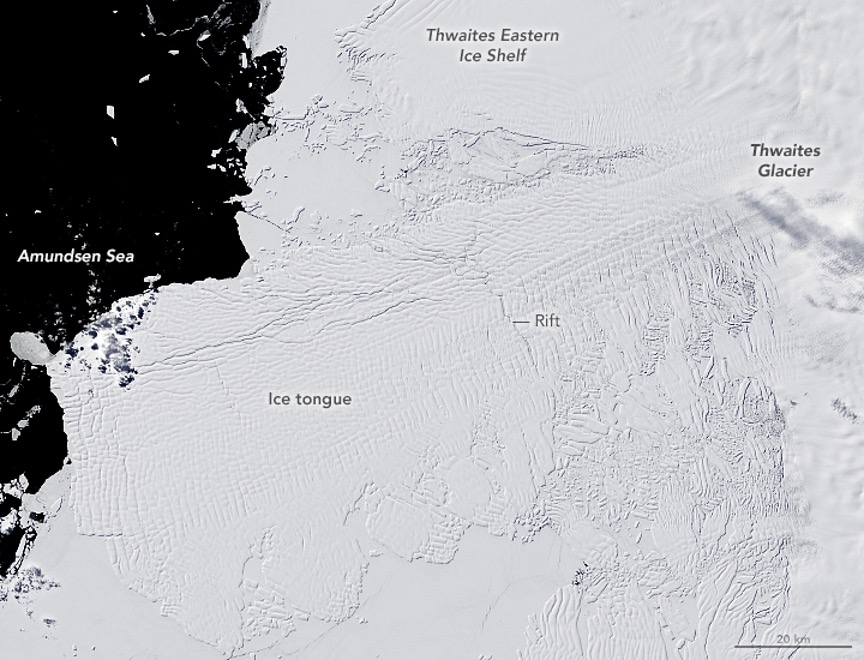

The glacier has an ice shelf — a permanent piece of floating ice connected to it — that branches out into the Amundsen Sea. Now, understanding what exactly an ice shelf does is crucial.

To visualize it, picture how pancake batter spreads out toward the sides of a pan when it is poured. Just like that process, snowfall in Antarctica falls on glaciers and packs into ice. The tremendous weight of all that ice can cause chunks to break off and flow down to the sea where they freeze and connect to the glacier still on land.

The cutoff point where a glacier is no longer located on top of land but rather is the ice shelf floating on top of the sea is called a grounding line. In the case of the Thwaites Glacier, the ice above its grounding line ranges from about 2,600 to 3,900 feet (800 to 1,200 meters) deep. Visualize that depth for the roughly 80-mile width of the glacier and you can see that’s a lot of ice.

That’s where the bad news starts.

The Thwaites Ice Shelf is braced against an underwater mountain located 31 miles (about 50 kilometers) offshore. That grip is helping to hold the whole of the Thwaites Glacier in place — essentially, keeping it from sliding into the ocean faster than it already is.

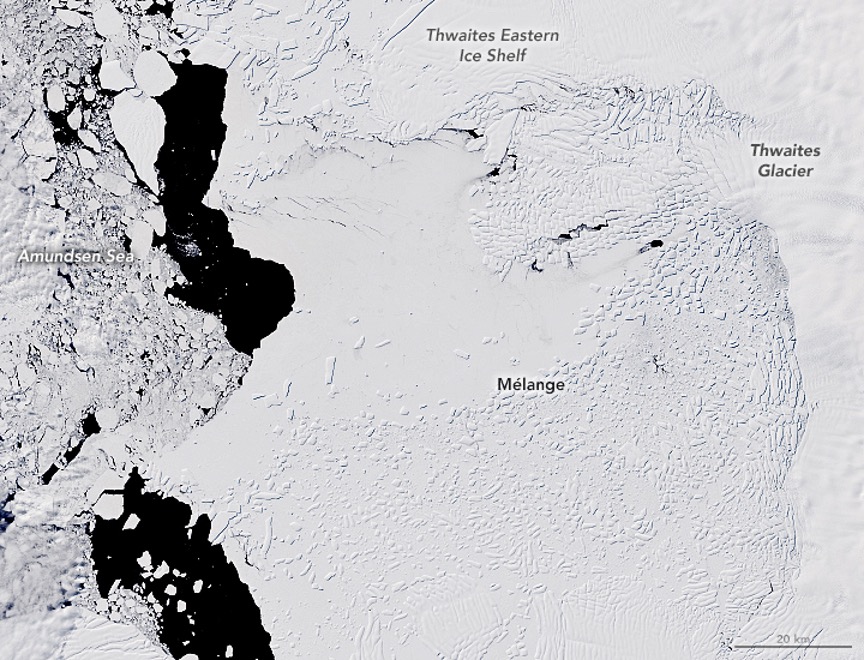

But as scientists have known for years, this shelf is melting and breaking apart, increasingly leaving the glacier access to slide into the sea.

Unlike the ice shelf itself, which is already in the ocean thus doesn’t cause sea-level rise, the glacier falling into the sea does add volume to the ocean and raise sea levels. Which brings us to the findings announced in December 2021.

WHAT RECENT RESEARCH REVEALED

Research published in December of 2021 by the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC) — the largest joint US-UK program of field science yet undertaken in the Antarctic — found that “the net rate of ice loss from Thwaites Glacier is more than six times what it was in the early 1990s.”

What’s more, satellite data shows that over the last 30 years, the flow of Thwaites Glacier ice across land and toward the sea has nearly doubled in pace. Annually, it’s losing about 50 billion tons of ice more than it is receiving in snowfall.

This all adds up to provide the key finding that the ice shelf holding back Thwaites Glacier from rapidly descending into the ocean could collapse in as little as five years. If that’s the case, then the resulting sea-level rise could rewrite the world’s coastlines irreversibly.

WHY IS THE THWAITES ICE SHELF BECOMING UNSTABLE?

Unsurprisingly, it’s all happening because of global warming.

Earth’s temperature has risen by 0.08° C (0.14° F) per decade since 1880, and the rate of warming over the past 40 years is more than twice that: 0.32° F (0.18° C) per decade since 1981.

As a result, all in all the average global temperature in 2021 was 1.1-1.2° C (1.98-2.16° F) above 1850-1900 levels.

Throw in the context that the world's oceans absorb a whopping 90% of that excess heat, and you can see why Thwaites Ice Shelf is collapsing.

In a nutshell: Warming oceans are eating away the ice shelf at the bottom, while rising average air temperatures increase melting above.

Thwaites Glacier, December 2001. Credit: NASA

Thwaites Glacier, December 2019. Note the broken-off ice in the Amundsen Sea. Credit: NASA

The world’s oceans were their warmest on record in 2021, for the third year in a row. And scientists don’t expect this trend to stop – especially if we continue polluting our atmosphere with planet-warming carbon emissions.

THE CONSEQUENCES OF THWAITES GLACIER COLLAPSING

Were Thwaites Glacier to fall into the ocean, it would raise sea levels by 65 centimeters, or more than 2 feet. This means rapid sea-level rise.

And that’s just the beginning. There’s a crucial climate change tipping point element to this threat. That’s because it’s collapse could lead to an ever-accelerating decline of the entire West Antarctic ice sheet.

As NASA has described, “this is the first step in a potential chain reaction.”

As “[o]cean heat eats away at the ice, the grounding line retreats inland and ice shelves lose mass. When ice shelves lose mass, they lose the ability to hold back inland glaciers from their march to the sea, meaning those glaciers can accelerate and thin as a result of the acceleration. This thinning is only conducive to more grounding line retreat, more acceleration and more thinning.”

In short, glaciers in Western Antarctica face the possibility of entering a vicious cycle of runaway melting that only promotes more and faster melting, over and over again. It's a feedback loop that could overwhelmingly escape our control, even if we were to cut our carbon emissions.

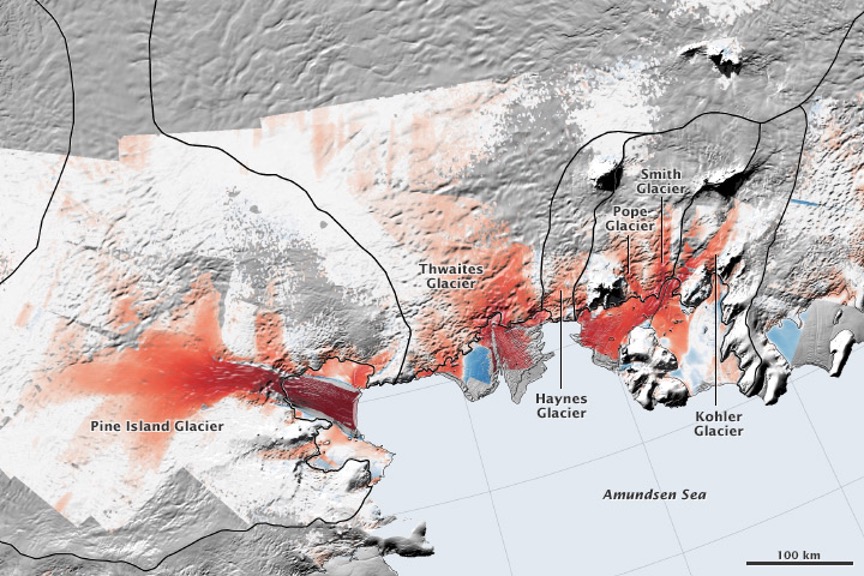

Glaciers in the West Antarctic ice sheet. Credit: NASA/GSFC/SVS

As previously mentioned, all the water in the Thwaites Glacier would raise sea levels by about 2 feet. However, if its collapse causes nearby glaciers like the Pine Island and Haynes Glaciers to more rapidly decline alongside it, then global sea levels could eventually rise by up to 10 feet.

A quarter of a billion people around the world people live within 3 feet of high-tide lines. Meaning the sea-level rise that Thwaites Glacier and other Antarctic glaciers would cause would, as one expert recently put it, be “a world-bending catastrophe. It’s not only goodbye Miami, but goodbye to virtually every low-lying coastal city in the world.”

IT’S TIME FOR REAL CLIMATE ACTION

The accelerating collapse of the Thwaites Ice Shelf, along with so many other climate impacts, makes clearer than ever what we already knew: that our climate is in crisis, and the time to work toward a sustainable future is now.

If you’re ready to take action, join our activist email list today! We’ll keep you posted on the latest developments in climate policy and what you can do to help solve the climate crisis.

By Diego Rojas